Second in a series

MANTEO – Yogi Berra came to mind as I sat among the old activists, who had gathered one night recently to plan for a fight they thought they had won almost three decades ago.

Michael McOwen sat in a chair on the other side of the living room, cradling his granddaughter in his arms.

I had first met McOwen in 1989 at Manteo Elementary School while covering a public meeting on Mobil Oil Corp.’s proposal to drill an exploratory oil well off the Outer Banks. He was holding his daughter, who was then about the same age as her daughter now in her grandpa’s arms.

“It’s frustrating that here we are again more than 25 years later,” McOwen told the others.

He stopped and looked at his granddaughter.

“But there’s a whole new generation now to fight for,” he said.

Yogi, a beloved baseball icon, a Hall of Fame catcher and an unintentional philosopher noted for his malapropisms, famously summed it up once. “It’s like déjà vu all over again,” he said.

McOwen and most of the others in the room had, indeed, been here before. The grassroots group they formed in the late 1980s, LegaSea, had been instrumental in galvanizing public opinion on the Outer Banks against the Mobil proposal. They were successful then after several years of fighting, but their vanquished enemy had arisen.

Grandmothers and grandfathers now, they met to regroup for a new fight, this time against the federal government’s recently announced plan to open much of the East Coast, including offshore North Carolina, to oil and natural gas drilling. It’s the first time since the Mobil days that drilling off the N.C. coast may again be a reality.

Some of the old activists had brought along some reminders of those old days – the cardboard box they used to collect donations; the bumper stickers, buttons and T-shirts with the “Save Our Oceans” and “No Offshore Drilling” messages; the newspaper clips and flyers.

“It brings back a lot of memories,” noted Lucille Lamberto-Egan, who now lives in Salvo on Hatteras Island, “and not all them are good.”

They shared some of those memories: the packed public meetings, wearing out U.S. 64 on drives to Raleigh to cajole legislators, the prickly governor who slowly became an ally, the phalanx of lawyers and public-relations people that Mobil threw at them, trips to Washington to meet with federal officials, senators and representatives; and the wreck of the Exxon Valdez that turned the tide.

“That history is important,” McOwen noted, “so we remember what we had to do and what we’re now up against again.”

Manteo Wildcat Well 467-1

The 1973 Arab oil embargo triggered gasoline shortages and long lines at gas stations across America. In response, President Richard Nixon ordered his Department of Interior to triple the amount of offshore acreage available for oil and natural gas exploration.

For the first time, the East Coast was in play. Oil companies bought leases in 1976 and again three years later for tracts off the Northeast coast. They drilled 10 wells. All were dry or contained non-commercial quantities of oil or natural gas.

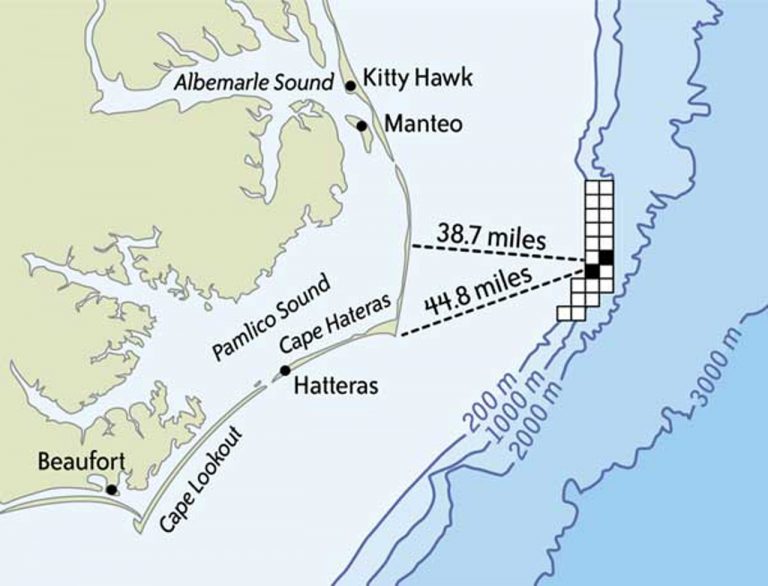

Given that track record, the bidding war that erupted when the first tracts in the south Atlantic were sold in August 1981 surprised many. Sale No. 56 became a landmark for East Coast leasing because of the aggressive bidding by a three-company partnership of Mobil, Marathon Oil and Amerada Hess. It bid a record $103.8 million, or about $266 million in current dollars, for one nine-square-mile block, called 467-1 on the map, that was about 35 miles east of Salvo. The partnership along with five other companies also leased 20 other adjacent blocks for $260 million — about $667 million in 2015 equivalent dollars.

The eight companies formed the Manteo Exploration Unit and chose Block 467-1 as the best place for an exploratory well. It was at the edge of the continental shelf in more than 3,000 feet of water. Below it, buried deep beneath the seafloor, was a 100-million-year-old limestone reef that formed when the ocean was much lower than it is today. Porous limestone can make excellent traps, or reservoirs, for oil and natural gas.

The companies estimated that the reef could hold as much as six trillion cubic feet of natural gas, or the energy equivalent of a billion barrels of oil. That would have made it at the time one of the largest gas fields in the world.

As majority owner of the block, Mobil was named operator of the exploration unit.

Federal offshore leases normally give companies five years to explore, but most of the leases owned by the eight companies had 10-year terms. Longer leases were needed, the government reasoned, in so-called “frontier areas” where no infrastructure existed and where deep water, swift currents and other environmental conditions required greater lead times for exploration.

Mobil released the exploration plan for the Manteo unit in early 1989. Drilling was scheduled to start the following year.

Reaction on the Outer Banks was swift.

The Fight Begins

Michael McOwen had an ad agency in Manteo in 1988, the year he first heard of Mobil’s plan. His wife, Beth, had started the community’s first domestic-violence shelter. They had just had their first child.

“We were involved with the community in fundamental ways and cared about the Outer Banks,” he said, “but I don’t think anyone would have called us activists.”

That changed after he attended a meeting where a Mobil lobbyist explained the company’s plans. “It was the first time anyone had heard about this stuff,” McOwen said. “I was shocked.”

And so the organizing began. McOwen and other opponents formed North Carolinians for a Clean Coast. They later changed the name to LegaSea.

“Mobil meanwhile was taking to local politicians and leaders. They came back about how great it would be,” he said. “People told us ‘This is Mobil Oil. You can’t kick them out. They’ve got resources and politicians and lobbyists.’ We heard that a lot, but we just didn’t believe it. We just couldn’t envision this happening here.”

LegaSea’s first task, McOwen explained, was to find out more about offshore drilling and what it might mean to the Outer Banks.

Halfway across the state, then-Gov. Jim Martin had the same idea. Only the second Republican elected governor since Reconstruction, Martin was in the final year of his first term in 1988. A Princeton-educated chemist, he had taught chemistry at Davidson College before being elected. Like any good scientist, Martin wanted answers about what drilling might mean to his state.

Clark Wright was hired to get them. Wright was then a young lawyer in private practice in Raleigh. He had caught the eye of the state attorney general’s office after he successfully defended development permits at North Topsail Beach. An assistant called. Would he be interested in becoming the special counsel to the governor on offshore drilling? Wright told him that he knew next to nothing about the issue. He got the job anyway.

“That was literally my full-time job,” Wright said recently over lunch at a noisy restaurant in New Bern where he is now a partner in his own firm. “Nothing else was initially in my realm than the offshore drilling issue. That was an amazing time.”

For the next two years, he collected studies and reports on everything from offshore drilling techniques to Gulf Stream eddies. He interviewed the top scientists on the subject and toured offshore platforms in Mobile Bay in Alabama.

“I amassed a four-drawer file cabinet on everything,” he said. “The information I amassed helped us put together a pretty compelling case that we didn’t know enough about what Mobil was trying to do.”

A Game Changer

Federal law didn’t require companies to do full-blown environmental studies for an exploration well. Officials at Mobil and at the old Minerals Management Service, which at the time was the federal agency that managed drilling in U.S. waters, assured Martin that there had never been a major spill or accident at a test well. An environmental-impact statement, or EIS, they said, would be done if Mobil decided to pursue production wells.

Martin wasn’t persuaded and neither was he pleased that he had only 30 days to respond to Mobil’s drilling plan. In a handwritten note at the bottom of his formal letter to the agency objecting to the process, Martin wrote: “Unless you find some basis for a more patient and thorough approach to some of the major environmental fears, it forces us to adopt the most defensive posture at every turn.”

The company and the government ignored Martin’s demand. They learned what many legislators, reporters and staffers already knew. “Jim Martin did a good thing and said, ‘No. We need to know more,’” Wright said. “And the more Mobil got snotty about it, the more that man, who could be very stubborn, got his back up.”

There things stood on March 24, 1989, when the Exxon Valdez sailed into Prince William Sound on the southeast Alaskan coast a little after midnight and struck Bligh Reef. The tanker was carrying about 55 million gallons of crude oil from Alaska’s Prudhoe Bay oil field. As many as 25 million gallons ended up in the remote sound, covering 300 miles of shoreline and killing an untold number of wildlife. Oil from the Valdez was still washing up on beaches 470 miles from the sound more than a year after the accident.

The effects in North Carolina were more immediate, noted Derb Carter, who heads the Southern Environmental Law Center’s office in Chapel Hill. At the time he served on a task force that Martin empaneled to study the Mobil proposal.

“The Exxon Valdez happened in the middle of all this,” he said. “It was significant because it was a pretty stark demonstration of what could happen if a similar spill happened on the N.C. coast. Even though it was a tanker spill, it focused pretty dramatically what the effects of a spill could be.”

Martin called a press conference in Raleigh less than a week after the accident. I stood at the back of the packed room in the Administration Building. A Mobil lawyer and public relations guy stood next to me.

The governor approached the podium. He didn’t look happy. Martin wasted little time in announcing that the state would seek an injunction to stop Mobil’s drilling plan.

“And then we’re going to sue you,” Martin said, pointing to the Mobile guys.

He took a few questions and strode purposely out of the room.

The lawyer and PR guy looked stunned.

“What the hell just happened?” the PR guy asked.

“The Exxon Valdez,” I replied.

This Is the End

Martin got his study after Mobil and the government agreed to a voluntary process that mimicked an EIS. Opposition mounted in the seven months that it took to complete the study.

“Some of the bigger communities like Morehead wanted the staging business,” Wright remembered. “Most everybody, even the business folks, were appalled at the idea of seeing the Outer Banks become Louisiana.”

Despite the study, which was completed in 1990, state officials still argued to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration that year that they didn’t know enough about drilling’s effects to determine if the Mobil proposal was consistent with North Carolina’s coastal-management program. A positive review was needed before Mobil could get federal permits for their project.

“No one had ever won a consistency appeal dealing with offshore drilling,” Wright said. “There were several that had been tried, but they always lost to the trump card in that process, which is national security. It has a veto factor over any other issue.”

Mobil appealed to the U.S. secretary of the Interior, who agreed with the state.

It was over. U.S. Rep. Walter Jones Sr., a Democrat who represented the Outer Banks, pounded in the final nail when he successfully added the Outer Banks Protection Act to an appropriations bill in 1991. It barred drilling off the N.C. coast until a long list of studies was completed.

Mobil waved the white flag and then went to federal court to get its leasing money back. There, it won.

“We were all committed to seeing this through,” McOwen said as the meeting wound down that night in Manteo. “It turned out that the people of the Outer Banks didn’t need much prodding. Opposition was nearly universal. You know that famous line in the movie Field of Dreams: ‘Build it and they will come’? We built it and they came. Now we have to rebuild it.”

Wednesday: The long, winding federal process.